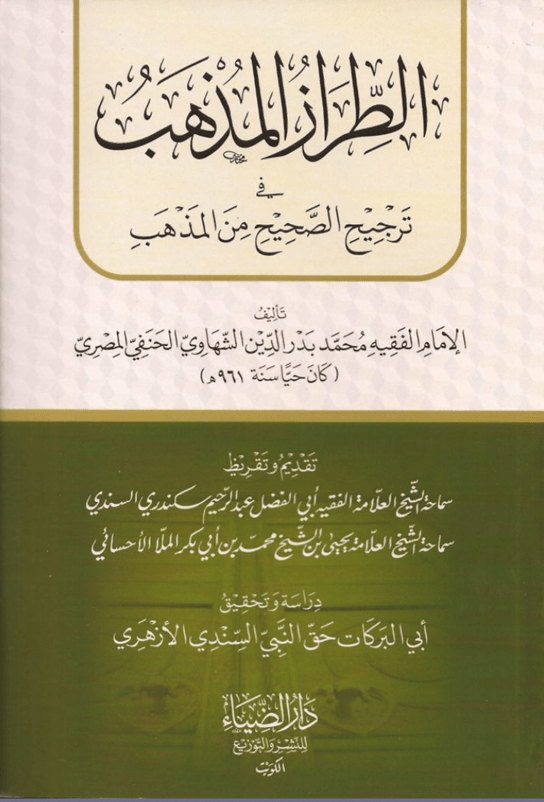

In this seminar, Dr Talal Al-Azem (Cambridge Muslim College Academic Director) outlined the trajectory on the madhhab-law tradition after the Islamic empire’s rule shifted from Damascus and Cairo to the Ottoman East between the 15th and 18th centuries. The presentation focused on an unstudied 16th century epistle of Badr al-Dīn al-Shahāwī (d. 961/1553) entitled ‘al-Ṭirāz al-Mudhhab fī Tarjīḥ al-Ṣaḥīḥ min al-Madhhab’ (The Robe of Royalty, Embroidered with Gold, regarding How to Establish the Correct Position of the Madhhab), focusing on how jurists were meant to discover a madhhab’s legal rule, following the main processes of rule-formulation (tarjīh) and rule-review (taṣḥīh). Through his epistle, al-Shahāwī’s readers are given rule-discovery techniques especially when dealing with a disagreement between the madhhab’s latter-day scholars (mashāyikh) when there is no explicit text (naṣṣ) on the question at hand from the earliest scholars in the clearly transmitted works (ẓāhir al-riwāya).

Rule Discovery Heuristics for the Associate

In his epistle, Shahāwī addresses six main areas of rule-discovery for the less trained jurists or associates: (1) how to discover the ruling; (2) the vocabulary of rule-discovery; (3) the formal procedure of the jurist (rasm al-muftī); (4) the probative value or relevance of fatāwā works that contravene the madhhab’s primary works (uṣūl); (5) non-mujtahid muftis (those who are not qualified to interpret the Law) are bound to the opinion of Abu Ḥanīfa; and, (6) all opinions of the founding scholars are in reality alternative opinions of Abu Ḥanīfa, which they have transmitted, unless due to change of age and times.

With special focus on the fourth area, Al-Azem highlights that, based upon al-Shahāwī’s directions, fatāwā questions which were already established and confirmed by the primary opinions (uṣūl) of the madhhab and recorded in the early scholars’ normative works ought to be followed and any later contrary opinions or ‘explicit statements’ to be dismissed. In doing so, al-Shahāwi contests Qāsim Ibn Quṭlūbughā (d. 879/1474)’s approach to rule-determination, which gives ‘explicit statements’ a greater probative value. In his work, al-Shaḥāwī seeks also ways to: (1) identify the strongest and most correct transmissions based upon a hierarchy of texts/genres; (2) determine the most suitable position based upon time and place; and (3) review the jurisprudential principles upon which the madhhab-law tradition operates.

What this demonstrates, Al-Azem explains, is that the madhhab-law tradition is, unlike the common law tradition, a juristic law, probabilistic and pluralistic (as open to multiple interpretations and madhhab jurisdictions), and exploratory yet ‘conservative’ in its scholastic approach (in order to honour and preserve the centuries-long juristic precedence). Al-Azem points out that many of the problems encountered in the rule-discovery process were due to the lower ranking jurists’ ignorance of and lack of skill in navigating the early scholars’ books and imperfect mastery of their operative principles, leading readers to consult the wrong books for answers. Consequently, in his treatise, al-Shahāwī includes Ibn Kamāl Pāshā (d. 940/1536)’s ‘Typology of the Jurists’ (Ṭabaqāt al-fuqahā’) establishing the seven degrees of jurisprudential ability and eligibility.

Dr Al-Azem has thus illustrated that, in his epistle, al-Shahāwī directs lesser trained jurists to consult books containing clearly transmitted opinions (ẓāhir al-riwāya) to discover the fatwa position, unless latter-day scholars agree on change. Similarly, fatāwā works that contravene the madhhab’s primary works (uṣūl) are to be disregarded but may be used when dealing with an unaddressed issue.

In the second part of the seminar, participants posed important questions surrounding the value of later fatāwā works in the field and the fundamental distinction between statements (aqwāl) and transmissions (nuqūl). As Al-Azem explained, later fatāwā works were not deemed problematic in themselves as long as the opinions were not attributed to the Imam’s position of a given madhhab. Nonetheless, al-Shahāwī’s position does beg the question, left unanswered in his treatise: namely, if all early positions were attributable to Imam Abu Ḥanīfa, how are different opinions from the Imam’s own companions to be reconciled? Further research into the reception of al-Shahāwī ‘s work, and the madhhab-tradition more generally, may uncover the resolution to this and other theoretical and procedural questions in this rich tradition.

For more information about the Cambridge Muslim College Research Seminar, see here.

As Academic Director of Cambridge Muslim College, Dr Talal Al-Azem heads the College’s academic programmes, leads in the development of curricula, and oversees research. He was educated at the University of Michigan and at Oxford, and studied the disciplines of Islamic learning in Syria and Turkey. Dr Al-Azem has served as fellow at the Oxford Centre for Islamic Studies and lecturer in the Faculties of Theology and Religion and of Oriental Studies at the University of Oxford. His research focuses on Muslim moral theology, law, and education.